Codepoint: U+10FB "GEORGIAN PARAGRAPH SEPARATOR"

Block: U+10A0..10FF "Georgian"

The Georgian scripts are encoded in four letter forms in three Unicode blocks:

The four rows are:

- Asomtavruli is the oldest form, dating from the fifth century CE

- Nuskhuri dates from the ninth century CE

- Mkhedruli is the current Georgian script

- Mtavruli is the uppercase version of Mkhedruli

In the original "Georgian" block, the codepoints U+10A0..10C5 encode the uppercase of the old ecclesiastical alphabet, Asomtavruli (row 1). The codepoints U+10D0..10F0 encode the the lowercase of the modern secular alphabet, Mkhedruli (row 4). The latter is used for almost all text, including at the beginning of sentences and names.

However, don't be tempted to mash together uppercase Asomtavruli with lowercase Mkhedruli to get a bicameral script. That problem wasn't "solved" until the addition of the later "Georgian Extended" and "Georgian Supplement" blocks. More on that in later posts. For modern Georgians, this isn't really a problem at all; writing uses only one case.

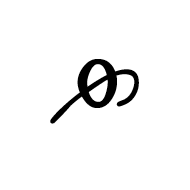

In old texts, the "჻" symbol (U+10FB GEORGIAN PARAGRAPH SEPARATOR) was used at the end of the last line of a paragraph. Its use was presumably similar to that of the pilcrow "¶" but at the end of the paragraph, not at the beginning. Alas, the Georgian script didn't get its own full stop; it must share it with the Armenian one, "։" (U+0589 ARMENIAN FULL STOP)

ISO 10586:1996 encodes 42 characters of the Georgian script in a 7-bit character set, including the paragraph mark at 0x4F.

There is an interesting annex in the standard, part of which I'll include below:

Annex A: Development of the Georgian script

Armenian and Georgian, two of the multitudinous tongues spoken in the Caucasian Region, are vehicles of millennial civilizations. Both languages present peculiar phonetic resemblances in spite of their completely different origins. Georgian, or Grusinian, is a member of the Kartvelian language family. Armenian is a member of the Indo-European language family. Each language has its own alphabet, which resemble one another, since the alphabets developed from the same source.

According to one tradition, these two alphabets were invented circa A.D. 406 by the Armenian monk, missionary and theologian Mesrop Mast’oc’ (ca. A.D. 360 to A.D. 439), who also invented an alphabet for the now extinct language Albani (or Caucasian Albanian). According to another tradition, the Georgian script was invented circa A.D. 300 by the Georgian king, Parnavaz. Some scholars allege that it was invented many centuries earlier. The origin of, and the relations between, the three forms of the script are also still in dispute.

More likely, the Georgian script was derived, as was the Armenian script, from a Semitic alphabet, the Pahlavi script, used in Persia in the 4th century. It was developed under a strong Greek influence (by Mast’oc’ or perhaps one of his disciples) into an alphabet enabling the Georgian people to spell their language, with its wealth of sounds in a simple and phonemic way. Owing to phonetic evolution, a few letters became superfluous. In former times, the Georgian alphabet was also used in writing Ossetic and Abkhaz. The oldest inscription in Georgian dates back to the 5th century. The oldest manuscripts date from the 8th century. The period from A.D. 980 to A.D. 1220 is considered the golden age of Georgian literature.